Monthly Artist Feature with

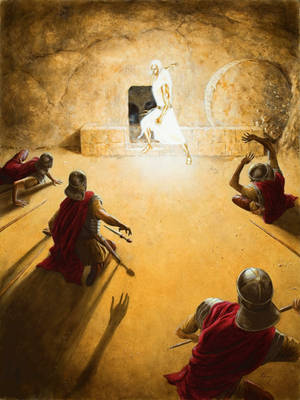

Each month we would like to feature one of the many gifted Christian artists in christians. Our artist of the month is DouglasRamsey. In a world where traditional painters are a rare breed, Douglas Ramsey's Biblical paintings are like a breath of fresh air. His motivation and humility are an example to all of us who desire to serve God with our art. We hope that you enjoy reading his thoughts.

We would like to thank you for taking the time to do this interview! First we would like to ask, How did you get started and why did you come to love art?

I started drawing when I was about three years old, like everybody. As far back as I can remember people have complimented me on my drawing ability, although looking at those early drawings today, I’m not sure exactly why. They seem like the kind of stuff you’d expect from any child. Anyway, I heard it often enough to believe it but I figured that in the wider world outside my small-town existence, I wouldn’t be anything special. Throughout my childhood, adults would kid me about how they wanted one of my pictures since, some day, it would be worth something, once I became a “famous artist.” This puzzled me since I didn’t know of any famous artists, at least not ones that were still alive. Where I grew up in Florida it was common to see well-painted landscapes of the beaches but I had no idea who had created them. Painting common scenes like that certainly didn’t seem like a path to fame or fortune.

The so-called “fine art” world wasn’t any more inviting. By the time I was 8 or 9 years old I would get jokingly asked by other kids if I was an “abstract artist.” I would firmly say, “no,” but really, I had no idea what they meant. I was completely unaware of the dark, relativistic philosophy that modern “fine artists” had embraced. What I did know was that, to me, most of the work I saw hung in respected galleries looked mud-fence ugly. It was weird, chaotic, and seemed to require absolutely no skill at all. Only the “educated” or “enlightened” could appreciate its genius. Evidently, I wasn’t in that category because its genius escaped me completely. Even then I got the sense that the emperor had no clothes and I certainly had no intention of dedicating my life to creating more of the stuff. Bottom line, there didn’t seem to be a well-lit career path laid out for me in the world of art so I eventually began training for an academic one in the world of archaeology and Biblical studies.

To make a long story short God eventually uprooted me from that situation and put me where I’m at now, not quite as dramatically as he did with Jonah. I didn’t get swallowed by a whale, (though I did spend about three years of my life sailing around the ocean on a submarine, which is probably the next best thing). That came about through a variety of circumstances and looking back on them today, I could see the years I spent in the military and graduate school as a long detour away from what I should have been doing all along. But in the providence of God I think they were actually necessary preparation for what I’m doing now. In his book “Traditional Oil Painting”, Virgil Elliot warns that it would be a serious mistake to assume that techniques and materials are all there is to great art. “All the technique in the world cannot guarantee that an artist can be great if he or she has nothing to say. Great art depends heavily on content.” I think this was my basic problem with art when I was a teenager. I had some natural ability but I didn’t really have much to say. Traveling the world and getting a formal education in my subject matter was probably a better use of my time in the long run than training in art techniques would have been.

How did you learn to paint?

I’m still learning how to paint. To this day I feel like I don’t know what I’m doing every time I start a new painting. Up to this point though, I’d say most of what I’ve learned has come through trial and error. When I was six years old my grandmother used to take me to an after-school art class but these were cut short when our family relocated so I didn’t get beyond learning how to draw in various dry media in those days. In fact, I never really painted at all prior to my teenage years and initially I would just copy work by other painters as best I could. In the process I gradually got a feel for it as I became familiar with how the paints would respond. I’ve cannibalized various techniques and tricks from lots of guys and as you try different things out it somehow morphs into what instinctively works better for you. Ultimately I don’t think that’s something that can really be taught. It’s just the product of the time you have to put in yourself at learning your craft.

Your art has a very distinct look. How did you develop this style and how would you describe it?

Hm. I suppose I just gave up on consciously trying to develop a style. When I was young I noticed how different artists would usually have a very recognizable “look” to their work. You could tell who painted or drew it pretty easily. I was pessimistic about developing any signature style of my own because I had no idea how it was achieved. All I knew how to do was draw what I could see in front of me. This was one of the things that initially discouraged me from even pursuing a career in art as it wasn’t until much later that I realized most artists don’t consciously invent a style for themselves, it just happens. Its distinctive elements aren’t necessarily intentional. They’re mainly the product of an artist’s unique thought process or way of seeing things in their mind’s eye combined with their individual fine motor skills. In other words, it comes out of what they’ve filled their heads with. Your visual imagination is something that’s very much influenced by the kind of imagery you collect with your eyes, from other artists or movies or real life experiences, etc. All of those things are absorbed and tossed together into the blender of your own imagination and what comes out is something that’s your own and works for you. That’s a long way of saying that, for me at least, it’s pretty instinctive.

How do you achieve the illusion of movement in your paintings?

Exaggeration. One of the earliest art instruction books I read (back in the mid-80’s) was “How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way” which gave some great examples of how to give your figures a more dynamic look by making their movements bigger and more angled than you’d actually see in real life. I remember, when I was a boy, noticing some comic character’s exaggerated stance and suddenly realizing that no human being would normally position their legs that way in real life. Although I’d seen this type of pose many times before, I had somehow never thought to question it. When you’re dealing with 2-D art things have to be enhanced a bit just to look real.

This kind of thing is especially necessary when you’re creating a sense of motion in still pictures, I suppose because we don’t see moving things frozen in real life. It may be that in the time your eye moves from one part of the painting to another it expects the character to have moved, for its limbs to be farther apart, as they would in real life. At least, that’s my best guess as to what’s going on. To capture that you can’t just show things as they would actually look in a stopped piece of film. You have to enlarge their movement a bit. For example, something I learned from Bryan Hitch, is that if you want to draw someone running fast, don’t use a photo of someone who’s actually running as your reference. It almost always looks stiff. Instead use someone who’s ice skating or rollerblading to get a greater sense of speed.

This can easily get too extreme though, at least for my purposes. Since most of my work is depicting historical subject matter rather than fantasy, I want it to have a realistic look and to achieve that it’s got to have a basis in reality. Joe Kubert has noted that if you’re mainly learning to draw from other artists, especially ones who are working in an exaggerated style, you can quickly veer into over-exaggeration. So today we have artists who are piling exaggeration on top of exaggeration by copying Marc Silvestri, who’s copying John Buscema, who’s copying Hal Foster, who did Life drawing. Studying real life helps keep my work somewhat grounded in it.

Where do you look for inspiration?

Deadlines. They’re typically considered to be the bane of great art but more often than not it’s the “need” for inspiration that can be the real enemy. That’s the main difference between a professional artist and a hobbyist I suppose. If you’re only doing art for the fun of it obviously you can just do it when you feel like it. If you’re going to make a living at art you have to treat it like a job. You can’t passively wait around for the mood to strike because sometimes it just doesn’t come. You have to be able to sit down and turn it on whether you feel inspired or not.

There’s an analogy here to spiritual discipline as well. We all go through spiritual dry seasons where we don’t feel like praying or reading the Bible or going to church. We can rationalize that, since our heart doesn’t take much delight in those things right now, we might as well abstain from them until it does. Do them anyway. I liken it to digging irrigation channels in a dry field so that when the spiritual rains finally do fall, or the river overflows its banks, your field will be well-watered and ready to grow some abundant fruit.

Do you have some favorite artists (on or off deviantART)?

Too many to list here. Due to the rise of postmodern weirdness though, the modern descendants of past greats have largely been driven out of the “fine” art world and into the world of illustration. More recently, much of illustration has dried up as well, so that many of the most talented draftsmen have been funneled into comic books. A lot of these guys probably wouldn’t have even considered working in comics a few decades ago but today some of the ones I admire most are in that field.

Your faith in Jesus seems to be a common theme throughout most of your artwork. How do spiritual things come into play with your creative process?

Everything produced in the creative process is a reflection of the artist’s faith, thoughts, experience, joys, dislikes - all the things that make them who they are. That comes first. The pictures are the by-product. They flow out of your spiritual growth and progress in sanctification. For Christian artists, that involves imitating Jesus. I really can’t put it any better than Charlie Peacock does:

“True artists imitate Jesus in His serving and His storytelling. They pursue greatness in craft in order to give the Lord the best fruit of the talent He has given them, not to build themselves up…Other-centered living (after the model of Jesus) is at the very heart of good art-making. The arts have the ability to serve people in a number of healthy ways, from worship to our need for beauty. Care for others through your talent, and be imaginative about what caring and serving might look like. The possibilities are wide, high, and long.”

For more on this whole subject, I highly commend reading Peacock’s full article, “Art that is Fueled by Faith” which you can find at www.byfaithonline.com.

Please describe your typical workflow.

I always start with the story I’m trying to tell. I consider myself to be more of a visual storyteller than a painter of pretty pictures. Not that there’s anything wrong with painting pretty pictures, I enjoy that too, it’s just that storytelling is where my primary interest lies. So if I’m translating a literary text into a visual image, I just try to imagine what it would look like if you could travel back in time to witness that event happening. What I end up drawing is pretty much what you’d see. That’s all. Sometimes I’ll sketch several thumbnails or small comprehensives to explore different possibilities for camera angles and compositional arrangements, just to help me decide which one works best. This is the stage where I try to solve all the creative problems and determine what works and what doesn’t. If I try to bypass this step, I typically wind up doing it at the painted stage (not fun). Even if you have a pretty clear idea of how you want to do the picture it can be helpful to try a few alternatives just to assure yourself that this is the one you want to go with and avoid second-guessing yourself later on. I really should do color comps more often but I’m usually too impatient to get on to the actual painting.

After that I’ll study the text and research its elements, such as the setting, props, characters, etc. to make them look as accurate as possible. Depending on what I learn from this I might have to completely rethink my composition or tweak it here and there. Then I’ll try to take or gather up as much photo reference as I think will be helpful. It’s rare for me to get exactly what I want from the photo sessions so I’ll normally just take the best elements from them and conform them to my initial drawing. Working from photography can easily stiffen up your work if you don’t reinterpret it adequately so I use just enough of it to enhance the sense of realism that wouldn’t be there without it.

For a paintings I normally work on board, gessoed with light grey, either heavyweight illustration board or hardboard, depending on what size I need, so that I don’t have to deal with the texture created by canvas weave. I gesso the surface for two reasons: 1) It allows me to draw on the surface since gesso takes pencil very well and 2) since I create the original surface of the board I can always re-create that surface if I need to paint something out or back it off (in acrylic that is, don’t try it with oil). I use grey gesso so that I start in the middle of the value scale and don’t have to fight my way all the way down from the white to achieve the darker values.

I normally render everything in pencil pretty tightly, especially the elements that are the main focus. The drawing is the most important part of the painting for the type of work I do. If it doesn’t work, the painting fails, so I invest a lot of work on this stage. Sometimes I’ll do a fully tonal underpainting in black and white and then just add some layers of transparent color on top of it. This doesn’t always work when the paint is too opaque and sometimes obliterates the work done in the tonal layer to the point where I have to completely redo it in color. Other times I’ll just have a pencil outline and fill in all of the tonal values in the color stage.

Depending on the needs of the individual painting I’ll sometimes paint from the background forward, and sometimes I’ll paint the main figures first and the background last. Doing your foreground elements first, when working in acrylics, can help keep them from having that overly hard, unnatural-looking edge to their outline. My color process as a whole is just a slow build up of glazes and washes until painting finally works or just needs to be abandoned.

What is your process for photographing your paintings?

Well, the best thing to do is to take them to a good photographer and have them do it. It’s also the most expensive though, so I don’t recommend it unless the piece is something you think people will be interested in purchasing as a reproduction. You can take a good quality photo on your own though, if you have a decent camera. You just need the software and the know-how for manipulating it digitally to look more like the original (which I don’t). Probably the most helpful thing I’ve learned about the process is to avoid glare by using indirect, outdoor lighting.

What tools do you use? What is your favorite medium?

It actually depends on the piece and what will work best for the effect I’m driving for. Part of me would like to limit myself to just one medium and really master that one by itself but I also enjoy the variety of working in oils, acrylics, watercolors, ink, pencils, and even metalpoint sometimes. Inevitably, I get a little tired with working in just one, so it’s refreshing to change things up by switching to something else for awhile.

That said, acrylics are probably the most versatile and correctible physical medium. For that reason, if I’m doing a complicated piece with lots of figures it’s got to at least start in acrylics. It’s often said that they’re easier to use than oils and in many respects that’s true. They’re certainly easier to clean up and if you work in glazes and washes, as I do, you can finish a painting a whole lot faster with them without having to worry about long drying times or yellowing or cracking. But in other ways they can be a lot harder to use than oils. Their faster drying time is both an advantage and a disadvantage, as getting soft blends from them over large areas can be really difficult. It usually requires an airbrush for me to get the look I want with those. They also don’t have them same fullness or depth of color oils have unless you varnish them, so one method that’s worked well for me sometimes is to do the first several layers in acrylic and finish the piece in oil.

For art materials, I use a lot of Winsor-Newton’s products for both acrylics and oils, although I also use Golden and Liquitex brand paints for some colors. Winsor-Newton also makes most of the brushes I use, my favorite being the Series 7 sable rounds. You can get a nice fine line from these although you really shouldn’t use them for acrylics. Loew-Cornell makes good quality affordable brushes for acrylics. For hardboard I use Ampersand. For illustration board I normally use Crescent or Bainbridge when I need it cut to custom dimensions. I don’t use canvas often enough to have a favorite brand though Masterpiece makes the best canvas I’ve actually tried. For paper I usually go with Strathmore Bristol.

What is your daily routine like? Do you have any hobbies other than art?

It varies. I have a wife and two small children so their schedules dictates mine right now and I have to be flexible and work whenever I can. The ideal work day for me would be one similar to Rubens. He woke up early, had his prayer/devotional time (in his case hearing mass, in mine Bible study), sketched and/or painted until the afternoon when he got some exercise (for him taking a ride on “a fine Spanish horse”). My exercise comes from running, weight training, boxing, and playing with my kids (which is kind of like boxing sometimes, only you get to be the punching bag). I think it’s important for artists who spend a lot of time at their drafting table or easel to stay physically active with something, whether it’s sports or bodybuilding. If they don’t, many of them are going to end up overweight or develop other bodily ailments that come with a sedentary lifestyle. More than that though, if you want your art to have physical energy, that is, if you’re depicting scenes with action or fighting, then it’s creatively helpful for your body to understand that kind of physicality because it does translate itself into the work.

Which one of your pieces best defines you or your art?

Hopefully, one I haven’t created yet. I’m not trying to be evasive, I just don’t think there is one that does that by itself. Of course, I’m happier with the way some of them turn out than others but I’m probably better defined by my body of work as a whole.

What is the best thing about being a Christian artist and what is the worst?

That’s hard to rank but I think most of the difficulties that artists face boil down to their art being undervalued. It’s not uncommon today to see high quality work ignored and unappreciated while no-quality trash gets lavish praise thoughtlessly heaped upon it. And when I say trash, I’m referring both to work found in the supposedly high-minded world of “fine” art and to the stuff you get from the sappy, sentimental world of kitsch. It’s often said that modern-day people understand things better visually than verbally. I don’t think that’s quite true. People today may prefer pictures over words but only if they don’t say too much. Just because they’re visually oriented doesn’t mean they’re visually literate, as most people lack the ability to see even the most basic things that are communicated in pictures. Darkened hearts suppress the truth by their unrighteousness, whether that truth comes to them from their eyes or their ears. As John Calvin puts it, “People, immersed in their own errors, are struck blind in such a dazzling theater.”

On top of that, many churches don’t think of art as a legitimate way to serve God and function as the supportive community they should be. They have some justification for that attitude since art has certainly been used to promote values that are antagonistic to Scripture. The Church has learned to be suspicious of it. Ironically though, many Christians have actually gotten their negative attitude towards the arts from the secular world without realizing it. They’ve unwittingly bought into an aesthetic relativism that comes straight from postmodernity. In the past, the Church traditionally upheld the value of goodness, truth, and beauty, but today it’s been duped into devaluing beauty as something subjective and unimportant while still trying to hold on to truth and goodness. That just doesn’t work. All three are attributes of the living God and as such are inseparably linked together.

This is something I learned from Paul Munson and Joshua Farris Drake. The reason the (relatively new) saying “beauty is in the eye of the beholder” has become so widely embraced, even by Christians is that it insulates people from any form of objective criticism. It’s supposed to promote tolerance and respect but what it really promotes is indifference. After all, if beauty is nothing more than a matter of personal preference, then no piece of artwork is better than any other and I really have nothing to gain from studying or enjoying them. And so art becomes undervalued (or, in many cases of bad art, overvalued). This is one of the reasons artists can have a hard time trying to eek out a full-time living from their work. It’s frustrating, but it helps to keep in mind that many of the difficulties artists face are just part of working in a situation where the world resists our efforts to cultivate it (Gen 3:17-19). These difficulties are obstacles we should overcome, not complain about. If you go through life in a fallen world expecting it to be fair, you’re going to be waste a lot of time being angry and disappointed.

Perhaps the best thing about being a Christian artist is that you’re uniquely equipped to minister to a lost and dying world. Images do have an advantage over words today in that their impact can be immediate and lasting. In today’s world of diminished attention spans and electronic distractions it’s hard to get an audience for your verbal message, especially when it requires people to sit still and listen for a while. Art can cut through all that and arrest the viewer at first sight and even haunt their memory long afterwards. One of my goals when illustrating literary texts is to get the viewer interested in reading those texts. The pictures should be able to communicate some of what’s in the text in a unique way and on their own. As Philip Graham Ryken says, “Art has tremendous power to shape culture and touch the human heart. Its artifacts embody the ideas and desires of the coming generation. This means that what is happening in the arts today is prophetic of what will happen in the culture tomorrow. It also means that when Christians abandon the artistic community, we lose a significant opportunity to communicate Christ to our culture.”

Christians have a great advantage over unbelievers here, in that we know why we came into the world. We know the story of redemption, the story of God’s kingdom and how that larger story shapes our own. God’s revelation supplies the only satisfying explanation for beauty, in that it both defines beauty and explains why we respond to it emotionally even as it simultaneously guards us from idolizing it. The Christian artist knows that art which glorifies God is good, true, and beautiful. Preachers expound the special revelation given in the Bible. Artists expound the general revelation found in creation, and I’m not referring to artists who do biblical subject matter like mine (which crosses over into special revelation). Still life paintings, landscapes, abstract work, and so forth can all call our attention to the qualities of God revealed in the forms of “things that have been made.” To one extent or another, we all walk around numb to the glories that surround us and art can offer a means of “recovering sight to the blind” as it helps us actually see the subtleties and wonders of God’s handiwork. Participating in that is not only the best thing about being a Christian artist but, I think, the ultimate purpose of art itself.

In closing, please tell us 3 tips that are crucial for a Christian artist.

Know when to listen to criticism. You have to be careful in how you process feedback. I’ve seen a lot of gushing praise accumulated by work that ranges from mediocre to just plain awful (some of it my own). A lot of people just don’t know how to judge art. And in general, people want to be nice, at least in person. They aren’t always going to give you their honest opinion so you have to take a lot of what you hear with a grain of salt. Take it seriously though, whether negative or positive, when it comes from someone who knows what they’re talking about. If they point out ways you can improve, be receptive and don’t let it hurt your feelings. Everybody has room to improve and fails sometimes, even the best artists.

If you’re a professional, learn to think of yourself as a small business. Don’t work for free. I’m a Calvinist, so I know that people are sinners, and I believe in the total depravity of human nature and the universality of the sin and all of that. Yet it still amazes me how many people expect artists to work for free. Don’t let people take advantage of you like that. If you’re going to do something for free it might as well be something that’s entirely of your own passion.

Many (probably most) artists don’t know how to sell their work but this is a challenge that every small business faces. It’s not enough just to do good work and hope someone with money sees it on the internet. If artist’s websites aren’t promoted well, they just give you another place where you can remain undiscovered, this time in cyberspace. You have to aggressively market your art and what that involves will depend on the kind of work you’re producing. If you’re not an entrepreneurial type, that may require getting an agent or business partner that can better handle that end of things.

Make great art. Obviously this involves mastering fundamentals and honing your skills. But art is communication, so in order to make “great” art you need to first of all have something to communicate. You need something to say and that something has to be true. Postmodern art takes a kind of smug satisfaction in its willingness to tell the “truth” about how painful, ugly, and meaningless life really is, but their narrative lacks hope and this makes it incomplete and ultimately false. On the other end of the spectrum, supposedly “Christian” art often refuses to acknowledge the reality of the fall. It portrays a world sanitized from any damaging effects of sin where everything is bright, sweet, and sentimental and everyone is always happy, happy, happy. This type of art may have a kind of beauty but it also fails to tell the whole truth and people instinctively shun it as false. The Christian approach to art should avoid being either naively idealistic or pessimistically nihilistic. Christian art is philosophically realistic and redemptive. It mourns the destruction brought into the world by sin but also points to the way out through the hope we have in Jesus Christ.

Skin by SimplySilent